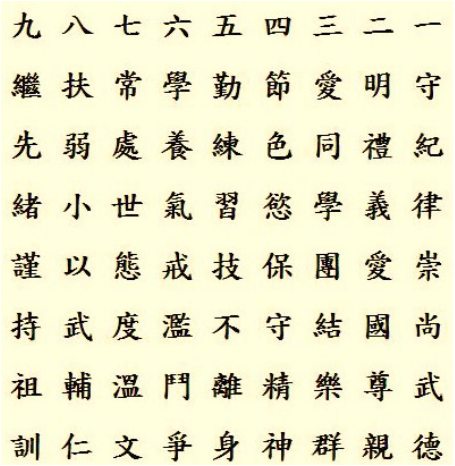

詠春祖訓

Ving Tsun Jo Fen

Authored by the Ancestors of Ving Tsun

Recorded by Grandmaster Ip Man and Ip Ching.

As a young boy, Grandmaster Ip Man studied the art of Ving Tsun (Wing Chun) kung fu and as he studied, he learned the rules of the art from his teacher. We are not certain if they were actually written down for him to see or if he just learned them as he learned Ving Tsun. It does not matter. What does matter is that Grandmaster Ip Man did leave us a written record of these rules, to be remembered and held on to, for all generations to come. These rules were engraved into stone and placed in the school for all the students to see. These rules have been studied by serious Ving Tsun students ever since.

Ving (詠) Tsun (春) Jo (祖) Fen (訓)

The rules start with this title: Ving Tsun Jo Fen. The characters “Ving Tsun” refer to the Chinese martial art by the same name. The other two characters in the title, “Jo Fen” are translated as “instruction of our ancestors”, “Jo” meaning ancestors and “Fen” meaning rules, instruction, principles, or patterns.

This book contains instructions from our Ving Tsun Ancestors. It is a record of some of what they knew and learned and a distillation of how we should treat Ving Tsun, or perhaps how we should treat life if we want to be part of Ving Tsun. It is, in one sense, the voice of the past speaking now for the future.

These instructions have been preserved, handed down, added to, (perhaps subtracted from) and continued on to repeat the cycle again. They are the accumulated wisdom of those who walked the path of Ving Tsun long before us, layer by layer making the rough a little more smooth like the accretions that form a pearl. We don't know who first wrote these principles down or whether there was a single author or many but do we know this: pearls should not be treated lightly; they are not easy to come by. These pearls formed over years among the surges and irritants of life and the ever present pull of Ving Tsun. They are not pre-manufactured, bite size nuggets of information to be gobbled up, digested, and excreted for you to move on to the next valueless meal of information.

And we hope with this book to show you that these rules are not just more information, more flotsam and jetsam in the deluge. They are a rarity today, not just information but hard-fought learning, not so much the next fad pushed by your local information peddler as real insights from real teachers, part of a fabric of a tradition. These rules are invitation to become part of a tradition, to recognize that wisdom, skill, judgment, martial ability are learned by the guidance of those who have walked before us. These rules are invitation to set aside our pretense that we can know everything ourselves (our pretense that if we just consume enough garbage we will be able to tell the garbage from the pearls) and be willing to be taught by many who have walked the path, gained the wisdom, and who want to show you the path of Ving Tsun.

The Ancestors that passed on these rules understood and took for granted that all men are capable of recognizing truth when they see it. They also understood that the best way to understand a rule is to get in and live with the rule. Consequently, there is no discussion about the step-by-step application of these rules. The rules are brief statements, aphorisms, if you will, that invite you taste the fruits of living the rules. The words that form the rules only point to the abundance that comes from living the rules. Can it be that in the end these rules can only be understood in the application of the rules?

We think so. And to that end we have authored this book not only to make the rules more widely available but perhaps by the commentary to sketch some of the richness in these rules in the hopes it will entice you to undertake living the rules.

In undertaking a commentary, we understand that we are also running the risk of reducing the abundance of the rules to a poverty of words. We caution you not to take our interpretation, our hints, traces, and sketches as final or authoritative. Live with the rules. Take from these commentaries what resonates with your experience of living the rules.

To do this you will need to learn to think beyond what is expressly said to what is left unsaid. For example, while the Ancestors wrote down the rules they did not write any consequences for those rules. This ought to strike you as a little odd. Natural or otherwise there are always benefits and consequences to every law and an entire range of consequences could flow from these rules ranging from sweeping the school floor, to not being able to continue learning from your Sifu, to the loss of your Kung Fu.

Since the Ancestors did not explain the consequences, we are left to discover what they are for ourselves and we are forced to discover for ourselves what the Ancestors knew when they wrote the rules: it is not necessary to explain the consequences because they follow from the rules. In following the rules, one becomes part of Ving Tsun. In disobeying the rules one becomes separated from Ving Tsun. It is, therefore, important that the art remains steadfast in its direction, undeviating in the course charted by these Instructions of our Ving Tsun Ancestors. To do otherwise is to lose Ving Tsun.

Yat 一

Sau 守 Gei 紀 Leut 律 Song 崇 Serung 尚 Moh 武 Duk 德

Sau (to guard) Gei (discipline) Leut (law) Song-Seurng (worshiping) Moh (martial) Duk (morality).

Discipline yourself to the rules (law), and keep sacred the martial morality.

The first part of rule number one:

What could it mean to discipline yourself to the rules? This part of the rule is a bit of a puzzle. What "rules" are we to discipline ourselves to? These rules? Some other rules? How can we discipline ourselves to rules if we don't know what they are?

These are natural questions but they aren't the right questions. Ask yourself why the Ancestors would phrase the rule this way, why they would tell us to discipline ourselves to rules and not spell out those rules. They didn't specify the rules because their audience already knew the rules. And so do we.

We are capable of choosing good from evil; we do not always need an external set of rules to guide us. We have a conscience, a universal sense of right and wrong and from it we know the rules we should live by. But you must take hold of yourself and discipline yourself to do what is right. You can't just make a checklist or grit your teeth and force your way through. If you have to consciously think of following the rules, you've missed the point. The point of discipline is to drive something into your bones, to engrave it on your heart. By discipline you come to follow your conscience from your heart.

This ability to see what is right and to discipline ourselves to it distinguishes us from the animals. They do as they must. We can do otherwise; we can do as we should until we simply would not do otherwise.

The Five Aspects of the Disciplined, Human Heart

For the Ancestors, the human heart that has disciplined itself to the right is distinguished from the animals by five aspects or principles. So before we turn to the second part of this rule, allow as a brief moment to sketch the following five principles that distinguish the human life from the animal life.

1. Yan 仁 Love

2. Yee 義 Righteousness

3. Lai 禮 Politeness

4. Jee 智 Wisdom

5. Sun 信 Faith

Yan - Love:

At the end of any journey you will find not only that your scenery has change but so have you. Journeys are like that; they cause change. The same is true for everything, including love. To love, means to first love yourself. As this love matures, it expands and you will be able to push this love to your family, then to your friends, then to your country and the world, even the plants and animals. So that when you see a dog walking down the street, you want to see it continue to live, when you see a river, you want future generations to see it too. This is Tai Yan (big love). It is the great journey. And when you reach this destination, you will love everything just as you love yourself.

At the end, the perfection of this Yan, you preserve nature because you see that you are part of it. If you see too few flowers, you will grow more flowers. You do this for nature and you find your nature is the same as the sky and the ground, bridging heaven (Sky means god) and earth (ground means nature). Realizing your place in nature and its role in your life is a very important part of traditional Chinese culture. It explains, in part, why the Chinese use herbs when they are sick rather than taking western pills. To them, the body is part of nature, part of what they love, not a machine to be tinkered with or overhauled but a treasured, living thing to be restored to balance. As the bridge between nature and the divine, humans who have come to the Tai Yan see not only their oneness with nature but their responsibility to watch over nature. They carefully watch the effects of their actions on the balance of nature. It is good, for example, to build buildings to help others live better but doing so destroys the ground. When we ignore this balance to build enormous homes, when smaller ones will do, or great luxury apartments, when simpler dwellings are sufficient, we have strayed from the proper way of love.

Yee - Righteousness (sort of like fair play):

You won't do the wrong thing if you have Tai Yan. When you do the wrong thing, you treat someone else differently than you would be treated; you treat someone else unfairly for your own gain. If you love your neighbor as yourself, you will treat your neighbor fairly. If your "neighbor" is all of humanity and all of nature, you will be fair; you will see the consequences of your actions on others and act rightly.

Let's take an example. You've decided to rob a bank, to take money from the evil corporate empire, and to give it to the deserving poor. Assuming you have no mixed motives, assuming you aren't, for example, keeping some of the money for yourself, is it right for you to rob the bank for this purpose? No. It's not just the "evil corporation" you are affecting. You might be taking money from a hard working man whose life savings will be lost because of your robbery. You might cost the security guard his job because he didn't stop your robbery. You might cost the teller her sense of peace because you pointed the gun at her.

When you have Tai Yan you understand you are not the center of the universe only a part of a network of connections that makes up the universe and you respect its sometimes fragile connections. Because you are not the center of this network, this web, you must understand the ripples your actions can have and act with fairness for the concerns of the others connected to you in this life.

Always remember that fairness is no small thing. People will fight for fairness; even give up their life for the right to be treated fairly. And when you understand this attribute of humanity and when you have Tai Yan, you will give up your life not only for the right to be treated fairly but for the right of others to be treated fairly. Animals fight for the right to live, one who has Tai Yan fights for the opportunity for others to live right.

Lai - Politeness:

Understanding righteousness, you will also be polite. Politeness is social virtue; it deals with the proper way for us to deal with each other, smoothing the friction that can arise between people in a society and polishing our relations. It presupposes that we are humble enough to respect each other-a humility that comes from Tai Yan.

This respect, this recognition of my place in the larger whole, and the humility that comes from it, extends not only to those who are present-not only to our parents or teachers-but also to those who are past, those who are dead but contributed to where we are today, and those younger than we are or not yet born since they will inherit what we leave for them. Politeness requires respect for everyone, past, present, and future.

This respect gives rise to a proper order of things. As the book of Lie tells us, an educated person knows proper social order. For example, in the old days when a boy went out with a girl he did not touch her hand. This was the proper way in those days; if the boy touched the girl's hand, he was rude. Politeness reflects the respect you have for others. By having good manners you avoid making people feel uncomfortable.

It would be natural to ask at this point: but how can I use wing chun if I am supposed to avoid making people uncomfortable? Doesn't punching someone make them feel "uncomfortable"? But politeness is not pacifism. In some situations, propriety calls for the martial artist to use his or her skills to protect those who are vulnerable. In thinking about this question you can see the dynamic tension that informs the way of life of a martial artist: respect for others that may lead to physical violence against another person; humility and selflessness that leads to courage; love that leads to fearlessness; fearlessness that is self-constrained.

Politeness is a social virtue; it presupposes that we stand in relation to each other, making this a good spot for us to take a slight diversion and discuss the relationships that are fundamental to a society.

Understanding relationships requires understanding that different people have different roles and the roles you have in relation to others can be varied. For example, although I am my teacher's student I teach others, so I am also a teacher. On this view, relationships are constructed based on our actions, our form of life, and not on some title or some mystical essentialism. Put another way, our relationships with others are more completely described by how we treat others than by a title or mental state.

The Ancients distilled the many actual relationships humans have with one another into four types or categories of relationships: King (also a leader or employer) who stands in relation to a subject (also a follow or employee); subject in relation to the King; father (or parent) in relation to the son (or child); and The son (or child) in relation to the father (parent).

Sometimes these four are described by four pairs of Chinese words: Gwan gwan, sun sun, fu fu, tze tze meaning, King, Subject, Father, Son. The first word "Gwan" is the subject and the second word "gwan" is the verb. So for each pair we have something like: King, act like a king. We see again that to be a king, is to act like one.

To these traditional four types of relationships, the Chinese have added three more over time: brother and brother, husband and wife, and friend and friend.

Each of these roles requires a certain attitude, a way of relating to the other person in the relationship. For example, if you are your father's son you cannot also be your father's father. So if you are the son you have to respect the father, or if you are an employee you have to respect the employer. This is another form of humility. It requires that we understand our limits. Though you become the employer or father to others, you are still your father's son or daughter and you are not your boss's boss.

Understanding this rule does not require slavish obedience. Rather, it requires the humility to understand that you may not know everything and that in certain roles you do not take the lead and in others you do. In certain roles, such as those of a son to a father, you don't give the advice, you listen to it. If you cannot bear to follow the advice of your father, you have stepped out of the role of son. This may be necessary in certain cases, but it is always a rejection of the role and an alteration of the relationship.

Thus, the subordinate should always respect his or her superior, i.e. the father or teacher. Even if you believe the father or teacher is wrong, out of respect you should still follow. And out of humility you should remember that you may not be completely fit to judge what is wrong. At a minimum, the respect for those who are in a superior position mandates that you at least find a respectful way of voicing your concerns and respectful questions will usually fit this bill. In short, if you think something is wrong your duty is to fix it from within the relationship not to overturn the relationship.

As a side note, traditionally a teacher was seen to have the same role as a father. Consequently, the student gave the same respect to his teacher that a son or daughter would give to a father. This also meant, however, that a student could not have more than one teacher, just as you cannot have more than one father.

We have touched briefly on the king-subject and father-son relationships, which are similar pairs of relationships requiring a superior/subordinate pairing. While these two types of relationship are similar they do have differences which derive mainly from the greater number of subordinates in the king-subject relationship. But it is this similarity in these relationships that leads Kung Fu-Tze to say, in the Great Learning:

“The ancients, who wished to illustrate illustrious virtue throughout the kingdom, first ordered well their own States. Wishing to order well their States, they first regulated their families. Wishing to regulate their families, they first cultivated their persons. Wishing to cultivate their persons, they first rectified their hearts. Wishing to rectify their hearts, they first sought to be sincere in their thoughts. Wishing to be sincere in their thoughts, they first extended to the utmost their knowledge. Such extension of knowledge lay in the investigation of things.

Things being investigated, knowledge became complete. Their knowledge being complete, their thoughts were sincere. Their thoughts being sincere, their hearts were then rectified. Their hearts being rectified, their persons were cultivated. Their persons being cultivated, their families were regulated. Their families being regulated, their States were rightly governed. Their States being rightly governed, the whole kingdom was made tranquil and happy.”

To this point, we have been talking about the essentially vertical relationships of king-subject and father-son. In those relationships, one is superior and one is subordinate. But the next type of relationship-brother to brother-is a mixture of superiority and equality.

Since brothers must care for each other and since both are subordinate to a father, there is an element of equality in a brotherly relationship that is not present in the father-son relationship. But brothers are not, strictly speaking, equals. An older brother has a stewardship to watch out for his younger brother and a younger brother should respect his older brother precisely because of that stewardship.

This brotherly love is called "Tai", while the love a child has for a father is called "How." Although these two types of love have differences, they share a similarity: both are prerequisites to developing Dai Yan (big love).

Why? Because it's easier to love those who have first loved us. Parents love us before we can love them back and as children we spontaneously play with and care about each other. There is no guarantee that these seeds of love will grow strong but the potential is there. And if we allow the seeds to take root, we cross over from animal reaction to human behavior. In the animal kingdom, the parents nurture and care for their offspring but when those offspring are grown they leave and don't nurture their parents in return. Animal siblings play together when young but may become deadly rivals when they are grown. So the seeds of love get planted but bear no fruit. To be human, we must learn at least to return love to those who have first loved us.

This is why How and Tai are stepping stones on the path to Yan. And this is why we should put more effort into developing How and Tai; you can't get to Yan unless you go through How and Tai.

The love between husband and wife goes beyond How and Tai, binding and connecting society. The merging of a husband and wife brings two families together, sort of like a king marrying a queen from another country or bringing the How and Tai love from one group and merging it into another group. For this love to bind there must be respect. The relationship between husband and wife can't be merely sexual it must be based on mutual respect. And this means that you must respect that individuals have their own personality. This respect, born of valuing differences, separates humans from animals.

We have now briefly touched on the king-subject, father-son, brother-brother, and husband-wife relationships and we can turn to the last type of relationship-friend-friend. This is relationship is different from the others. The other relationships we have spoken of so far are not completely a result of our choice. We do not choose our countries or our families. And even in a marriage, half of the choice is given to us, as the Ancients would say, from the sky or god. God lets two people meet and have feelings for each other-a reaction we can't entirely control. But while that is necessary for a marriage it is not sufficient because the other half of the marriage is something we have to work on, the relationship. Friendship, however, is different than these relationships. Who becomes your friend is purely a matter of your own choice.

So who exactly is your friend? Friends include the people who work with you, those who spend time thinking about the things that you do, and who do similar things as you. A Teacher and student might also be friends because the teacher encourages the student to study and they share the love of their subject.

The love of one friend for another is different than the other types of love because it contains no selfishness, no self-interest. In family there is continued shelter and protection even if you are in the wrong and in employment the hope of a paycheck. But in real friendship, the interest is purely spiritual, it is a shared interest. It transports knowledge from generation to generation.

Because a friendship is voluntary, you have to express your thoughts in a polite way. And even though a friendship starts with similarities, you must learn to trust and respect a friend's differences, so you can live with the differences. Because of this trust and respect, a friendship generates tolerance. Consequently, the more friends you have, the broader your horizons, and the greater the variety and richness of your life.

Jee - Wisdom:

We return now from our side note on relationships to the fourth aspect of the disciplined human heart, distinguishing good from bad. As we come closer to truth, we will see more clearly. As we see more clearly, we'll see errors we've made. When we see our errors we'll recognize them and make an effort to right them. So if I wrongly hurt you, I'll take you to the hospital, say I'm sorry, call you parents, and do all the necessary things to set it right.

But seeing our own errors and trying to correct them is only the first half of wisdom. Once we can see our wrongs, we will see the faults in others and we may try to teach them about their faults. Understanding the lessons from the past helps us find direction in life and, more than that, it helps us help others maintain a good path. When we pass on the wisdom learned from those who have gone before, including our own travails on the path, we show the next generation how to live a little better, thereby correcting our faults, making the world better, and ensuring that human society will progress toward truth.

Sun - Faith:

There must be faith for there to be action. If you don't have faith that your action will bear fruit, you won't act. And because you are human and know your frailties your faith must be in something larger than yourself: in a higher force, in principles, in the wisdom of the ages. Once you have wisdom, you must act in faith on the truth you have learned.

Keeping Sacred the Martial Morality: The characters Song Seurng together mean worship, whole hearted worship. This is not perfunctory ritual it is heartfelt devotion. This level of devotion will always seem slightly out of reach-as it should. If you could reach it with a few strides it would not compel you to keep traveling.

The second part of rule number one:

Moh Duk means martial morality. You must understand that a martial art is not only physical; it is also a way of approaching the world, a lens through which the martial artist sees the world. Only people who know martial arts will understand this. Martial artists live on a different plane from most people, because they have the ability to defend themselves. They must know when it is right to engage an enemy and when it is wrong. For example: after you learn how to strike and kill someone, your conscience will tell you to never correct little children by striking them because you may injure their small bodies. You know this; you feel the truth of it. When you are devoted to the martial morality, you won't beat someone up simply because they insult you because doing so would violate the morality woven into your sum fat.

These are moral rules and not a list of step by step actions. Keep that in mind. And don't worry that you won't know the answers; the answers are already in your heart. Be concerned instead that you will live the answers for they are lofty indeed.

Yee 二

Ming 明 Lie 禮 Yee 義 Oi 愛 Gwok 國 Juen 尊 Tsen 親

Ming (understand), Lie (propriety), Yee (righteousness), Oi (to love), Gwok (country or nation), Juen (to honor), Tsen (closely related people).

Understand propriety and righteousness, love your country and respect your parents.

There was a blind man who didn't know what the Sun was. So he asked other people to explain it to him. One man said, "The Sun is shaped like a copper plate.” So the blind man banged on a copper plate to hear the noise the sun might make. Later when he heard the sound of a temple bell ringing, he thought that must be the Sun.

Another man said, "The Sun gives light, just like a candle." So the blind man held a candle and memorized its shape. Later when he picked up a flute, he thought that this must be the Sun. We know the Sun is different from a copper plate or a flute, and yet the blind man did not understand the differences, because he had never seen the Sun he had only heard it described.

"Ming" means to understand in a way that allows you “to do.” Understanding and application cannot be separated. If we want to see if you understand something in mathematics, we ask you to solve the problem. If we want to see if you understand a principal in Ving Tsun, we watch to see if you demonstrate it in your Chi Sao. How can we claim to "understand" something if we can't do it or act on it?

For the Ancestors, the world was a place of order made so by the information in everything. This order is manifest in extremely large scales, like the universe, and in extremely small scales, like the sub-atomic. Witness how the information in your DNA shapes you. Makes you a human being and not a bird or duck or bear or beetle. The information in DNA leads to order: from the same building blocks arise different, consistent kinds. Without information the stuff of this world is just chaos.

If, as we have said, the world is ordered by information and understanding is doing, coming to understand that information leads us to live in harmony with that order. By understanding this universal, unchanging order, we make it “our order.” This is because as we understand we begin to live in harmony with this unchanging order, this wisdom. We can then teach others what we have lived. And knowing this information is part of the fabric of the world, we can be patient if others do not understand what we teach. If they are humble and will “listen and do” what we are teaching, because we have lived the wisdom, then they will learn. If, on the other hand, they do not listen and just “do”, then we can simply let go and not worry about it; knowing the order of things will confront them on all sides, and may one-day lead them back to learn again.

"Oi Gwok" means to love your nation. We use the term nation here rather than "country", since "nation" encompasses people and culture as well as geography. But why didn't the Ancestors ask us to love the world and not just our nation? Once again we come back to Tai Yan. For the Chinese, China is "Chong Gwok", the Center Country. If they loved their nation then they could love the rest of the world; having loved the center of the world, they could move out to the edges. If you can love your nation then you are able to love people you don't know and having expanded from those you know, to those you don't, you can learn to love even your enemies. But if you can't love where you are-your nation-you will never love the world. It is a simple progression of the Tai Yan.

The Juen character combined with Tsen means, "Respect and honor your parents." You can see that the first and second halves of this rule have the same pattern: order and propriety on a large scale (universe and country) and a small scale (person and family). Once again you must love where you are. Much of the order in your life, much more than you may now realize, comes from your parents. That should be no surprise; they are the source of your genes and they are your nation, your culture, your people.If you hate your parents, you hate yourself. If, on the other hand, you respect your parents then your life will grow with each passing day and shine brighter than the sun; you'll build on the order they have given you and, knowing your center point, you'll never get lost.

Sohm 三

Oi 愛 Tong 同 Moon 門 Tune 團 Guit 結 Lok 樂 Kuan 群

Oi (love), Tong (together), Moon (door), Tune (group), Guit (knot), Lok (happy), Kuan (group).

Love your classmates; enjoy working together as a group.

The phrase "Tong Moon" (literally "together door") refers to people who have come through the door together, in other words, the same learning family, those from the same Si Tai Gong, Si Gong, Si Fu. So "Oi Tong Moon" is a command to love your classmates, those who are in the same learning family. "Tune Guit" connotes pulling together and working with unity in a tightly banded group. And "Lok Kuan" means to stay happy while in the group.

Work can spring from either love or fear. Recent history has shown us that differences can be put aside to focus on a common enemy but when that common fear is gone, the differences re-emerge and former allies become enemies. It could be said that wars start because people cannot work together for the long term because they don't have a common love, a common focus.

In contrast, where people have a common love, where they are dedicated to the same thing and not just fighting against the same thing they can find ways to work together. If you love Ving Tsun and your classmate does too, you have a common objective, a greater purpose and it should bind you together.

Again we see echoes of the Tai Yan. If you love Ving Tsun, that love will grow and apply to those who walk the path with you. And if you love your classmates, you'll find a way of working out your differences and become united in your efforts. It is an organic process; give it time.

Furthermore, in this rule which directs us to work together and find unity, there is another message: there is strength and learning in numbers.

It is, for example, much more powerful for a group to move in one direction, guided by a mediocre idea, than for one person alone to move guided by a fantastic idea. Of course it is best if the group can be guided by a great idea. The strength of a group is that it has the will and resources to accomplish its idea and therefore, perhaps, great things. One man, alone, rarely accomplishes anything great.

There is a story the Chinese use to illustrate this idea. It is about an ancient warlord that had two sons.

One day the warlord asked both of his sons to do something, the thing is not important, and then left them to accomplish the task he wanted done. The two sons argued about the best way to accomplish the task. Their arguments grew louder and louder until their father heard their bickering. Knowing their arguments would only create an impasse, the father interjected. He took two arrows from his quiver and gave one to both sons and requested them to break the arrows in half. They both snapped the arrows without any problem. The father then took the remaining arrows from his quiver and gave them to the oldest son and asked him to break the entire bundle at once. The son pulled, twisted, and strained yet could not break the bundle of arrows, then his father asked his younger son to help is older brother, when both sons joined in they were able to break all the arrows at once.

The arrows represent a struggle; standing alone it is easy to accomplish an insignificant task, however when the task becomes large it is impossible to complete alone, one standing alone is weak and easy to defeat, however it is nearly impossible to defeat many people standing together as one.

Not only are you more likely to find victory in when joined with others for a common purpose but you are also more likely to find wisdom. When you like those in the group, you will open yourself to new thoughts and ideas. You will trust them enough to learn from them. Learn to be happy and grateful in the presence of others so you may learn things that are new to you.

The Chinese say "三人行, 必有我師 sam yan hang, beet yau ngoh si." Three people walking, one must be my teacher. What that means is, if there are a few people around me then there is always something I can learn from someone in the group.

Or there is this saying, "三個臭皮匠, 合成一個諸葛亮 sam go tau pei jeurng hop sing leet go Jue Gok Leurng". This saying has deep cultural roots. Translated it means three shoemakers together will become Jue Gok Leurng.

Jue Gok Leurng was the smartest man in Chinese history. During the time when China was split into three different parts, they were always at war. In the North lived Jue Gok Leurng, he taught his king many things. For instance, one time he was with the military fighting another section of China. This war included having to cross and fight over a very wide river. The people Jue Gok Leurng fought with were not very good at fighting on water and even worse they used up all their arrows. The situation looked grim indeed. Jue Gok Leurng thought and thought then came up with an idea. During the night he had all the men gather the grass along the banks of the river and bundle it so that the bundles would resemble a man. They placed these bundles in the boats and then all the men hid in the bottom of the boats. Early in the morning before the sun came up they began their crossing. Beating on the drums and yelling they fooled the other side into thinking they were attacking. The shocked enemy began shooting arrows into the grass dummies. Taking the arrows from the dummies Jue Gok Leurng and his men were able to replenish their arrows and eventually win the battle.

So three humble craftsmen, if they can learn from each other, "…can become Jue Gok Leurng." Learn and grow strong with your classmates

Say 四

Jie 節 Sik 色 Yuk 慾 Bo 保 Sao 守 Jing 精 Sun 神

Jie (control), Sik (apperance), Yuk (desire), Bo (to protect), Sao (to guard), Jing (perfect), Sun (spirit).

Control your desire and stay healthy.

Fate, as if to atone for the deaths of many people, and the hardships placed on millions more, destroyed an empire built around 247 BC when Chun Tsi Wong became emperor of China. As a thirteen-year-old prince, Chun ascended the throne of Ch'in after his father died. Within twelve years his armies had crushed most of the neighboring states. He had one overriding goal: To unify the country. It had never been done before. His passion drove him and as his power grew he began wanting more. His lust and greed for power overwhelmed his good sense. He ordered the burning of books on history except for Ch'in, folk collections of poetry and articles and books by scholars of schools with views different from those of the Ch'in, but books on medicine, agriculture, and copies of condemned books were preserved in the Imperial capital. He then arrested over 400 Confucian scholars, and had them buried alive. But his lust did not stop there; he also began to slip into insanity and paranoia overwhelmed him. So he began work on a wall that would surround his entire nation - the Great Wall of China. This insanity bred more insanity. To build the wall he needed money and lots of it, raising the taxes of an already impoverished nation and conscripting the eldest son of every household to go to work on the wall. If there were no sons then the father would have to work in his stead. This left only the elderly, the women, and children to run the farm so they could eat and pay his exorbitant tax. Even though Chun prophesied that his Empire would last 10,000 years it collapsed shortly after the Emperor's death sparked by a worker's rebellion.

Such is the story of lust. It can be found in every generation, in every nation, in every neighborhood, every family, even in yourself. And it is always dangerous.

Alone, "Jie" means "festival" but as used in this rule it is a verb meaning to control. "Sik" means appearance and "Yuk" refers to desire. So the first part of this rule is a warning: control your desire for sex.

Everyone has desire; it is not even uniquely human to have a sex drive. But having desires is not the point of this rule, controlling them is. It is our ability to control our natural instincts that separates us from other animals. We must be able to channel our desires, bending them to our ends. Understand it is not that the things we desire are themselves bad, nor is it that our desire is necessarily bad. It is that unbridled desire will destroy you.

"Bo" and "Sao" when taken together mean to protect and keep. Combined with the "Jing" and "Sun," the second half of the rule means to keep and protect a healthy spirit, or simply stay healthy.

So, the first half of the rule is to control your desires while the second is almost a promise. If you can control your desires then you will be, as Ben Franklin once said "healthy, wealthy, and wise." A little entertainment, enough sleep, sufficient good food, these are, in proper proportion good things. But sleeping 20 hours a day is just as damaging as sleeping only 2 hours a day. The Chinese say, "早睡早起精神好 Jo souie jo hay jing sun ho." which means early sleep and early rise makes your spirit healthy.

There are other activities which are enslaving and If you are enslaved by something, you may not have control over your desire and cannot have balance. Smoking is one example. Drugs are another. Some things should simply not be touched. They are traps ready to spring.

In short, if there is anything that will raise your spirit and cause joy then seek after that thing, but always in the right proportion. Where there is no balance there is no power.

Ng 五

Kun 勤 Lin 練 Tsap 習 Gai 技 But 不 Lay 離 Sun 身

Kun (work hard), Lin (practice), Tsap (practice or study), Gai (skill, but a negative prefix as in no or not or making something a negative), Lay (to go away from), Sun (body).

Work hard and keep practicing, so that the skills never leave your body.

You can't learn Ving Tsun just by watching or reading. The skills must become part of you and that only happens with repeated doing - with practice. As the Chinese say, "工多藝熟 Gong doah ngai sok," practice more and you'll be very good at that skill - practice makes perfect.

There is a story of Maai(卖) Yau(油) Yung(翁) (the elderly person that sells oil) that was written over a hundred years ago and remains an important piece of Chinese literature and which is still taught in Chinese schools today. In the past, when the people wanted to buy cooking oil, they couldn't go to the supermarket to buy a bottle of oil, simply because there were no supermarkets, so they would bring an empty bottle for the oil man to fill. This is a true story about an old temple master that sells oil—the story of Maai Yau Yung.

Many years ago, in China, the people spoke of a very wise old man that sold oil—a local Temple master. One day a very famous man, talented in archery, and very self absorbed, wanted to find this great master. Thinking to test this great master's talents, to prove that this master was ignorant and that he, the archer, was the greatest master of all times, the archer traveled to the temple where the master lived.

Once he arrived at the temple he found only an old, small, frail, bony man, just sitting there in unimpressive clothing. There was no great master in sight. The archer asked the old man for the wise master, and was surprised to hear that this unimpressive old man was the master he was seeking. More full of himself than ever, the archer turned to the old man and demanded, "Show me your talent." But the master declined.

So the archer, who, like all braggarts needed an audience, took out his bow and shot straight many times and never missed his mark. With a broad smile the archer finished his display of great talent and again demanded, this time with more anger in his voice, that the temple master must display his talents.

The master took an oil bottle, set a Chinese coin on top of it (in those days the coins all had a tiny square hole in the middle), scooped oil out of a jar with a spoon and poured the oil directly into the bottle through the coin. Immediately after pouring the oil into the bottle, the master took the coin and placed it in water as proof that no oil had even touched the coin (water would bead up on the surface of the coin if any oil had touched the coin).

The archer couldn't believe what he had just witnessed. He asked the master how he could have such a great talent. The master replied, "I sit here every day. Many people come to me and buy their cooking oil. I pour the oil into their bottle and they leave. I then repeat this to another customer day after day. I simply practice and practice more until this skill becomes part of me, my spirit. Great talent is the patience to practice those things which seem to be too small and insignificant to bother with, the desire to persevere to the end, and the wisdom that comes from that practice."

Practice is the great lie detector. Those who do not practice hard can deceive themselves into thinking that talking about Ving Tsun is doing Ving Tsun. But when you practice, you are what you are; no amount of verbal skills will change that. On the other hand, having stripped away the pretense in practice, you can begin to learn, to find the secrets by yourself. Until you have practiced hard, you don't even know what questions to ask your teacher. When you ask after having practiced, he or she is likely to simply refine how you are practicing and tell you to practice again. This refined practice will lead you to discover the answer, which you can then confirm with your teacher.

Practice is the currency of Ving Tsun. With it you buy real knowledge and with it you measure the cost of that knowledge. By measuring the cost of that knowledge to you, you see the value of your teacher's guidance in your practice; you see how much more this knowledge would have cost you without that guidance. From there it is a small step to understanding that you are not the greatest master of all time because your skill is an accumulation of many masters before you. You have reached your heights only by standing on the shoulders of giants.

When it is time for action, the time for practice has already passed.

Lok 六

Hok 學 Yang 養 Hay 氣 Gai 戒 Lam 濫 Dou 鬥 Tsung 爭

Hok (learn), Yang (nourish), Hay (vital energy), Gai (swear off), Lam (over use), Dou (incite), Tsung (fight).

Learn how to keep the energy and quit inciting a fighting attitude.

Learn how to nourish, use, and preserve your energy and stop inciting fights: this is how we have translated Hok Yang Hay Gai Lam Dou Tsung.

You must learn how to build, nourish, and use your vital energy. To do so, you must learn to control your emotions. There are 7 emotions: happy, angry, sad, surprised, love, hate, desire - Hay Low, Ngoi, Law, Oi, Wu, Yok. These emotions are related to one another, one leads to another, the other folds into the next. But the cycle can and should be mastered. There is a tendency in our western society to give full vent to our emotions because our emotions are perceived as more real, more true than thoughts or senses or ideas. But the presence of an emotion does not justify itself; that you are angry at someone does not guarantee that he has done something justifying your anger. You must study your emotions, understand their interrelations, know when to listen to them, and when to turn them aside. If you can harness your emotions, you will reap great benefits. If you can't bridle your emotions, you will sow only destruction.

You may be wondering by now why we are spending so much time talking about emotion when the rule doesn't mention it. Because emotions are the foundation of your energy, you must control your emotions before you can control your energy. There is something like a causal chain here: if you control your emotions, you control your energy. If you control your energy, you control your physical force.

It is easier for us to explain this principle than for you to learn to do it. You must put this part of the rule into practice and you must have a teacher who can guide you. Having said that, we will try to illustrate with one specific emotion - anger some of what it takes to learn to control the emotion.

To this point, we have discussed the emotions as the foundation of the energy. We have described them as being in a linear relationship: first the emotion, then the energy. But there is a feedback loop from energy to emotion and, in fact, learning to control the placement of your energy can be a powerful tool in learning to control your emotions.

As you begin to get angry for example, your energy will begin to rise to your head. If you feel your energy rising up from your center, bring it back down, center it. As you bring the energy down, you will notice the anger dissipating. It is not repression of the emotion but dissipation of its energy - the same principle we see in Ving Tsun over and over again.

If you let these emotions of anger or hatred or fear into your heart, if you lose your balance, it can be very difficult to regain. When you understand the energy cost of emotions running rampant and their possibility for destruction, you will nourish, control, and use your energy properly with the right emotion.

We have spent a lot of words on controlling emotions in order to preserve, nourish, and properly use your energy. But there are other ways in which you can waste your energy. Too much sex, as discussed in rule 4, will waste your energy. Improper eating, lack of rest, too much entertainment, too little training, all these things and many others can be wasteful of your energy. We cannot list all the ways you will need to safeguard your energy. You must simply learn to measure the effect of your actions, your attitudes, your thoughts, and your life on your energy and measure it against this principle.

The second part of the rule is tied closely to the first and is, in fact, another specific avenue for nourishing or preserving energy. The second part of the rule requires you to swear off fighting or inciting fighting. By fighting we don't mean only actually coming to blows, we also mean a fighting attitude, a chip on your shoulder. It is clear, fighting when there is no need to fight is just as wasteful of your energy as being angry at a wall or writing love poems to a duck. There is no point to using your energy in this way.

Do not use your kung fu unnecessarily. You may use it, should use it, when there is a reason. But you must have the wisdom to see when there is a reason. Just because someone wants to hit you, you don't need to use your kung fu unless you need to protect yourself. Just as you can abuse drugs and waste your life in the process, if you overuse or abuse your kung fu you waste your energy in the process. Stop using your kung fu just to hurt someone. If someone kicks your car, don't use your kung fu to beat them up, just call the police. Or if your kids break the TV, don't use your strength and hit them, use your strength to talk to them. People use violence too much and the ancients, through this rule, are telling us to stop. If you want to see this problem, you need look no further than Chi Sao; too many students just want to hit too hard. This is not the way.

As you can see from the Chi Sao example, your obligation under this second part of the rule also extends to others around you. You must avoid inciting a fighting attitude in others. When you go to classes do not always try to hit your classmates. When you are only trying to hit your classmates, you will lose your work out partners; no one will waste time trying to help you since all you want to do is hurt them. The concept here is that you always try to help your kung fu brothers and sisters get better. The stronger students should lower themselves to help the weaker students. In this way, everyone gets better, moves up one notch, and not down a notch. And when those you train with get better, you get better.

The entire rule might be summed up in this way: use the energy that is called for, no more, no less. There is an old story about a cook who understood this principle.

A cook was butchering an ox for Duke Wen Hui. The places where the cook's hand touched or his shoulder leaned against, or his foot stepped on, or his knee pressed upon, came apart with a single sound. He moved the blade, making a noise that never fell out of rhythm, harmonizing like music from ancient times.

Duke Wen Hui exclaimed: "Ah! Excellent! How is it that your skills have advanced to such a high level?" "What I follow is Tao", said the cook putting down the knife, "which is beyond all skills. When I started butchering, what I saw was nothing but the whole ox. After three years, I no longer saw the whole ox. Nowadays, I meet it with my mind rather than see it with my eyes. My sensory organs are inactive while I direct the mind's movement. It goes according to natural laws, striking apart large gaps, moving toward large openings, following its natural structure. Even places where tendons attach to bones give no resistance, never mind the larger bones!"

"A good cook goes through a knife in a year, because he cuts. An average cook goes through a knife in a month, because he hacks. I have used this knife for nineteen years. It has butchered thousands of oxen, but the blade is still like it's newly sharpened. The joints have openings, and the knife's blade has no thickness. Apply this lack of thickness into the openings, and the moving blade swishes through, with room to spare! That's why after nineteen years, the blade is still like it's newly sharpened."

"Nevertheless, every time I come across joints, I see its tricky parts, I pay attention and use caution, my vision concentrates, my movement slows down. I move the knife very slightly and Whump! It has already separated. The ox doesn't even know it is dead, and falls to the ground like mud. I stand holding the knife, and look all around it. The work gives me much satisfaction. I clean the knife and put it away."

Duke Wen Hui said: "Excellent! I listen to your words and learn a principle of life."

Chat 七

Seong 常, Chu 處, Tsai 世, Tai 態, Doe 度, Wan 溫, Man 文

Seong (always), Chu (to deal with), Tsai (life, or the world), Tai (attitude), Doe (degree), Wan (warm), Man (culture).

Always deal with problems using a kind attitude that is calm and gentle.

"Seong Chu Tsai" means "always deal with life or all people." If the rule stopped here, there would be no problem living it. We all deal with people every day. That, then, is not the challenge; the challenge is how to deal with people.

The solution is remaining constant: do unto others, as you would have them do unto you. If you don't want people to be rude to you, don't be rude to them, if you don't want people to be angry with you, don't be angry with them. If you want people to be kind and gentle to you then you should be kind and gentle to them.

This constancy leads to equanimity. Since you don't know everyone's character, you treat everyone in the same fair manner. As human beings we tend to be afraid of what is different or unknown. As a martial artist, you cannot. If you are rude to someone because they are a stranger, you may make an enemy out of a potential ally—a needless enemy. And such enemies, the ones we don't see, are very dangerous. These enemies, needlessly made, can be very close, even at your back. And if you make an enemy and put him at your back, even the best kung fu in the world will have trouble saving you.

"Tai Doe Wan Man" means calm attitude. You must have a gentle or calm attitude to be a gentleman. In the old days of China, gentlemen wore shirts with very long sleeves that would reach to the ground. A gentleman had to be conscientious, calm, and focused not to let those silk sleeves touch the dirt. You must also be conscientious, calm, and focused to treat everyone in a kind and gentle way. It takes no great strength to do what comes into your mind.It takes great strength to deal with problems with a calm and gentle attitude. Even and perhaps especially in small gestures, there can be much strength and great kindness.

The Ching Emperor, Kin Long, was the last Emperor whom the people really liked, even though he was a mandarin and not really Chinese. When the Emperor Kin Long was younger he was a great and wonderful king, very kind and very gentle. When he became Emperor, he always wanted to know what the people needed. He and his general would disguise themselves businessmen from Beijing and go to a town or village to see how the people were doing. Since he wanted to be treated like a normal person he would sometimes got lost and became a beggar or do hard labor to make money to stay alive. And once he was even thrown into jail. On these trips he never revealed he was the Emperor. He was so kind and gentle that no one ever suspected that he was the Emperor even though felt he was special because he was intelligent. Everyone liked him and helped him because he was such a gentleman.

One particular time while with his General in a restaurant, the Emperor poured a cup of tea for his officer. (In those days when the Emperor did something for one of his subjects, that person would have to show respect by bowing low as if to touch their head to the floor in a show of appreciation.) The General did not know exactly what to do, he could not say thank you in the traditional way—doing so would expose the Emperor. The General thought and thought, then came up with an idea, he began tapping his middle finger on the table as if to bow down and say thank you. To this day people will show politeness by tapping the table every time someone else serves them tea.

Bot 八

Fu 扶 Yuk 弱 Siu 小 Yeung 讓 Mo 武 Fu 輔 Yan 仁

Fu (to help), Yuk (weak or feeble), Siu (small), Yeung (to allow), Mo (martial), Fu (to assist or to help), Yan (humane or to love - it is the Yan from the big love, Dai Yan).

Help the elderly and the children and use the martial mind to achieve Yan.

Often, older people need a cane or some other instrument to help them walk. This support helps their balance and makes their footsteps more sure. Children too, especially as they are learning to walk, need a hand to support and guide them. And even when they can walk quite well they need a hand to protect and direct them. This is the charge from the ancestors to us: help, support, the weak and the small.

Why? Because you are a martial artist not a thug. Your martial skills are meant to strengthen society not weaken it. You have received a great gift in being privileged to receive Wing Chun. You did not develop the art. You have not yet been the one to preserve it but you are the one who received it. To keep it bright you owe a duty not only to the art but to those around you to protect the weak and the small.

How? By using "Mo" - your martial mind to achieve Yan. So martial mind (Mo) is means to becoming a humane person-Yan yan, 仁人. The first yan refers to the big love and the second means to be humane (same sound different words). The discipline and creativity of a martial mind leads one to become Yan yan and, therefore, to protect the weak and the small.

This rule is permeated with the thought of Gong Fu Tse and the following passage of his may even be the inspiration for this rule. As Gong Fu Tse said, "老吾老以及人之老, 幼吾幼以及人之幼, Low mm low yee kup yan gee low. Yaow mm yaow yee kup yan gee yaow." Love and help the elders in your family then push this love out to love other elders. Love and support the children of your family and then use this love to extend out to other children.

The Ancestors, however, go one step farther than Gong Fu Tze in this passage. He does not tell us how to accomplish this feat. But the Ancestors tell us the means by which we can do this thing: by using "Mo."

Above, we referred to "Mo" as a type of "mind." But it is a broader and stronger notion than that.It is a code of honor, a way of life, a type of morality, or a type of mind. If the phrase had not become trite by overuse and misunderstood because of misappropriation by thugs, we might say that "Mo" is a warrior spirit. "Mo" is the morality of one who appreciates life and protects it because he has studied violence and understands it and its limits. Think of Ip Man’s grand teacher,” Leung Jan, he was a Traditional Doctor in Fatshan, China, who could both kill and heal.

In our day, violence has become a game, a pastime. For one with the martial mind, violence is not and must not become an amusement. It is a tool in the service of life. It is a fire: capable of both destruction and light.

If you study Ving Tsun and do not increase in your respect for life, you have become a fighter not a warrior.

Kow 九

Gai 繼 Sin 先 Souie 緒 Gun 謹 Chi 持 Jo 祖 Fen 訓

Gai (to follow), Sin (before), Souie (Ancestor), Gun (serious or careful), Chi (to hold), Jo (also means Ancestor), Fen (rules).

Follow the rules laid out above, and follow the ancestors rules sincerely.

Tatxmg and Wangwu are two mountains with a large area of seven hundred li square rising to a great height of thousands of ren. They were originally situated south of Jizhou and north of Heyang. North of the mountains lived an old man called Yugong (literally 'foolish old man') who was nearly ninety years old. Since his home faced the two mountains, he and his family had to take a roundabout route whenever they went out. And this troubled Yugong so he gathered his family together to discuss the matter. "Let us do everything in our power to flatten these forbidding mountains so that there is a direct route to the south of Yuzhou reaching the southern bank of the Han River. What do you say?" Everyone applauded his suggestion.

His wife voiced her doubts. "You are not strong enough even to remove a small hillock like Kuifu. How can you tackle TaTxmg and Wangwu? And where would you dump the earth and rocks?"

"We can dump it into the edge of the Bo Sea and north of Yintu," said everyone.

Therefore Yugong took with him three sons and grandsons who could carry a load on their shoulders. They broke up rocks and dug up mounds of earth, which were transported to the edge of the Bo Sea in baskets. His neighbor, a widow by the name of Jingcheng, had a posthumous son who was just at the age of discarding his silk teeth. This vivacious boy jumped at the chance of giving them a hand. From winter through summer the workers only returned home once.

An old man called Zhisou (literally 'wise old man') who lived in Hequ, near a bend of the Yellow River, was amused and tried to dissuade Yugong. "How can you be so foolish? With your advanced years and the little strength that you have left, you cannot even destroy a blade of grass on the mountain, not to speak of its earth and stone." Yugong from north of the mountains heaved a long sigh. "You are so obstinate that you do not use your reason. Even the widow and her little son do better than you. Though I die, my son lives on. My son produces a grandson and in turn the grandson has a son of his own. Sons follow sons and grandsons follow sons. My sons and grandsons go on and on without end but the mountains will not grow in size. Then why worry about not being able to flatten them?" Zhisou of Hequ stayed silent.

The god of the mountains who held a snake in his hand heard about this and was afraid that Yugong would not stop digging at the mountains. He reported the matter to the king of the gods who was moved by Yugong's sincerity. The king commanded the two sons of Kua'eshi, a god with great strength, to carry away the two mountains on their backs: one was put east of Shuozhou and the other south of Yongzhou. From that time onwards no mountain stood between the south of Jizhou and the southern bank of the Han River.

Follow the previous 8 rules and sincerely (or wholeheartedly) maintain the ancestor's instructions. To be sincere or wholehearted, this is the key. Yugong's sincerity moved mountains. Only wholehearted dedication can do that; only wholehearted dedication to Ving Tsun is worthy of her.

Remember that you are part of Ving Tsun not the whole of it. Learn from your Sifu. Always come back to his teaching. If anyone shows you something different, take it to your Sifu. It is not just a matter of whether something works but whether it is part of the path of your Ving Tsun. Remember that you, your Sifu, your Sigung, and the Ancestors are moving the mountain. Hold the course and do not let your sincerity waiver. Do not leave the path for the seductive fruit of quick knowledge and self aggrandizement. We all like to believe we know something someone else does not. In so thinking however, we cannot be wholehearted because we are holding something back.

Do not let the perfectly reasonable skepticism of Zhisou of Hequ turn you from your unreasonable task of moving mountains. Take up your tools and head back up to the mountains where your Sifu, your Sigung, and the Ancestors have labored.